|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black Pigs Dyke

Black Pigs Dyke The Black Pigs Dyke, Aghareagh West, Co Monaghan

Straddling counties Monaghan, Cavan, Louth, Armagh, Leitrim, Roscommon, Longford and Donegal it is almost impossible to summarise the Black Pig's Dyke in a few paragraphs. It's extensive rows of massive banks and ditches are amongst the oldest, largest and most celebrated land boundaries in prehistoric Europe. In addition, interpretation of these linear earthworks have also proved to be the most elusive.

Although quite scattered, the popular public understanding was that they formed a cohesive and unified boundary for the ancient kingdom of Ulster, a monumental frontier defence that divided the province from the rest of Ireland. Theses views are now disputed by modern archaeology.

The earthworks are also associated with a widespread folk tradition about a cruel schoolmaster with magic powers who was transformed by one of his students into a mystical giant black pig and chased across the countryside, leaving in his wake a large track before drowning in a lake.

For a number of reasons little was done, until relatively recently, to interpret the Black Pig's Dyke and other associated earthworks such as the Dorsey and the Dane's Cast. In the past 30-40 years much has been accomplished by archaeologists in understanding the enigma behind their purpose and, although some interesting proposals have been made, there is still much to be uncovered.

The view shows construction of the Aghereagh West section of the Dyke, one of the best preserved and clearly visible lengths in County Monaghan.

Although quite scattered, the popular public understanding was that they formed a cohesive and unified boundary for the ancient kingdom of Ulster, a monumental frontier defence that divided the province from the rest of Ireland. Theses views are now disputed by modern archaeology.

The earthworks are also associated with a widespread folk tradition about a cruel schoolmaster with magic powers who was transformed by one of his students into a mystical giant black pig and chased across the countryside, leaving in his wake a large track before drowning in a lake.

For a number of reasons little was done, until relatively recently, to interpret the Black Pig's Dyke and other associated earthworks such as the Dorsey and the Dane's Cast. In the past 30-40 years much has been accomplished by archaeologists in understanding the enigma behind their purpose and, although some interesting proposals have been made, there is still much to be uncovered.

The view shows construction of the Aghereagh West section of the Dyke, one of the best preserved and clearly visible lengths in County Monaghan.

For more information visit http://www.monaghan.ie/en/portal/

Image ©Monaghan County Council - Please respect this right

Bronze Age Farm

Bronze Age Farm Bronze Age Farm, Clare Island, Westport, Co Mayo

Details to follow

Image ©Clare Island New Survey - Please respect this right

Corrstown Aerial View

Corrstown Aerial View Bronze Age Settlement, Corrstown, Portrush, Co Antrim

Details to follow

Image ©Portrush Heritage Group - Please respect this right

Corrstown Street View

Corrstown Street View Bronze Age Settlement, Corrstown, Portrush, Co Antrim

Details to follow

Image ©Portrush Heritage Group - Please respect this right

Dungiven Fort

Dungiven Fort Dungiven Fort, Dungiven, Co Londonderry

Details to follow

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Golan House

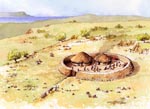

Golan House Golan Bronze Age House, Omagh, Co Tyrone

During upgrading of the A5 Omagh to Strabane road an interesting bronze age settlement was uncovered.

It showed the remains of a large round house which was of double walled construction with a gap of approximately 0.3m between the inner and outer wall. The walls were likely of posts and wattle, with the gap between most likely filled with insulating material or packed earth, to form a stable, secure wall, strong enough to help support the roof. The predecessor of the modern cavity wall.

The outer and inner faces of this wall would have been lined with daub, which would have also helped to insulate, and protect the timber elements from the weather.

The house was also found to have been surrounded by a palisade, probably of split timber construction.

It showed the remains of a large round house which was of double walled construction with a gap of approximately 0.3m between the inner and outer wall. The walls were likely of posts and wattle, with the gap between most likely filled with insulating material or packed earth, to form a stable, secure wall, strong enough to help support the roof. The predecessor of the modern cavity wall.

The outer and inner faces of this wall would have been lined with daub, which would have also helped to insulate, and protect the timber elements from the weather.

The house was also found to have been surrounded by a palisade, probably of split timber construction.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

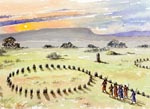

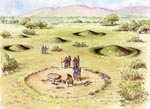

Ballygawley Henge

Ballygawley Henge Ballygawley Timber Henge, Ballygawley, Co Tyrone

During upgrading of the A4 Dungannon to Ballygawley road an interesting Bronze Age timber circle was uncovered.

The site comprised of a rectangular area, believed to be an entrance, leading into a larger circular area, itself containing a smaller concentric circle and a central group of upright timbers.

It is thought that these areas were reserved for various groups, with the inner circle being for the small group participating in the ceremony and the surrounding circle for observers. The rectangular area is suggested here as being for later hospitality with supplies being carried up along the approach path.

A number of large pits were found within the inner circle and these are thought to have been for votive offerings. It is also thought that some of the upright timber poles would have been painted, as shown at the entrances and in the inner circle.

The site comprised of a rectangular area, believed to be an entrance, leading into a larger circular area, itself containing a smaller concentric circle and a central group of upright timbers.

It is thought that these areas were reserved for various groups, with the inner circle being for the small group participating in the ceremony and the surrounding circle for observers. The rectangular area is suggested here as being for later hospitality with supplies being carried up along the approach path.

A number of large pits were found within the inner circle and these are thought to have been for votive offerings. It is also thought that some of the upright timber poles would have been painted, as shown at the entrances and in the inner circle.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Annaghilla Site

Annaghilla Site Annaghilla Metal Working Site, Ballygawley, Co Tyrone

During upgrading of the A4 Ballygawley to Enniskillen road an early medieval metal working site was uncovered.

The site had been occupied during the Neolithic and Iron Age periods and the surrounding medieval ditch had to some extent followed the lines of the earlier areas. A number of kilns and hearths were also found and our view shows men working at one of the kilns in the foreground.

The small timber huts would have been for fuel storage and a burial ground is shown in the background. This is common in the early medieval period where graveyards and ecclesiastical buildings were often side by side with industrial areas.

The site had been occupied during the Neolithic and Iron Age periods and the surrounding medieval ditch had to some extent followed the lines of the earlier areas. A number of kilns and hearths were also found and our view shows men working at one of the kilns in the foreground.

The small timber huts would have been for fuel storage and a burial ground is shown in the background. This is common in the early medieval period where graveyards and ecclesiastical buildings were often side by side with industrial areas.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Log Boat Site

Log Boat Site Log Boat Site, Dungannon, Co Tyrone

During upgrading of the A4 Dungannon to Ballygawley road the remains of what are believed to be of a log boat dating to the Mesolithic period were found.

Although the site was not close to water, subsoil maps indicated that there was once a stream that flowed to a nearby lough.

Logboats are essentially hollowed out whole or half-split logs, shaped both internally and externally. They are known to have been used in Ireland since the late Mesolithic or very early Neolithic, with an example from Lough Neagh, Co. Tyrone dated to 5490–5246 BC.

Our view shows a family using the log boat to access a favourite gathering location. One can imagine that the boat became stranded and had to be left in the area it was ultimately found.

Although the site was not close to water, subsoil maps indicated that there was once a stream that flowed to a nearby lough.

Logboats are essentially hollowed out whole or half-split logs, shaped both internally and externally. They are known to have been used in Ireland since the late Mesolithic or very early Neolithic, with an example from Lough Neagh, Co. Tyrone dated to 5490–5246 BC.

Our view shows a family using the log boat to access a favourite gathering location. One can imagine that the boat became stranded and had to be left in the area it was ultimately found.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Burnt Mound Site

Burnt Mound Site Burnt Mound Site, Loughbrickland, Co Down

During upgrading of the main A1 Belfast to Newry road a number of sites were discovered, particularly around Newry and Loughbrickland.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd and one site uncovered was a Burnt Mound in boggy ground near Lough Brickland.

Burnt Mounds are named after the residue left from the practice of heating stones in a fire then plunging them into a trough of water. The hot water was used mostly for cooking but also for Sweat Houses, as indicated here. Periodically the shattered stones and other detritus would be cleared out of the trough and deposited nearby, forming a crescent shaped mound.

A pot was found within the remains of the Sweat House conveniently dating the site to around 3500 BC.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd and one site uncovered was a Burnt Mound in boggy ground near Lough Brickland.

Burnt Mounds are named after the residue left from the practice of heating stones in a fire then plunging them into a trough of water. The hot water was used mostly for cooking but also for Sweat Houses, as indicated here. Periodically the shattered stones and other detritus would be cleared out of the trough and deposited nearby, forming a crescent shaped mound.

A pot was found within the remains of the Sweat House conveniently dating the site to around 3500 BC.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Newry Timber Circle

Newry Timber Circle Newry Timber Circle, Newry, Co Down

During upgrading of the main A1 Belfast to Newry road a number of sites were discovered, particularly around Newry and Loughbrickland.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area around Newry, where the remains of a timber circle was found.

The circle had two entrances and opposite these was what is understood to have been a screened off area containing cremated remains. The site is believed to originate from the Middle Neolithic period, however appears to have been constructed over an earlier ring ditch.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area around Newry, where the remains of a timber circle was found.

The circle had two entrances and opposite these was what is understood to have been a screened off area containing cremated remains. The site is believed to originate from the Middle Neolithic period, however appears to have been constructed over an earlier ring ditch.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

Brickland Site

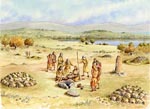

Brickland Site Brickland Barrow Site, Loughbrickland, Co Down

During upgrading of the main A1 Belfast to Newry road a number of sites were discovered, particularly around Newry and Loughbrickland.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area to the south of Lough Brickland itself, where they uncovered two late bronze age barrow cemeteries.

The cremated remains of 22 men, women and children were recovered from the cemeteries. The artefacts found include whole pottery bowls, polished stone axes, and flint arrowheads. The archaeologists also found evidence for what these prehistoric people ate, in the form of pig bones, apple seeds and carbonised grain.

This view shows the complexity of the cemetery with a body laid out on an excarnation platform, exposed to the elements and birds as part of the funeral process. Men are keeping the site tidy and working on one of the barrows.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area to the south of Lough Brickland itself, where they uncovered two late bronze age barrow cemeteries.

The cremated remains of 22 men, women and children were recovered from the cemeteries. The artefacts found include whole pottery bowls, polished stone axes, and flint arrowheads. The archaeologists also found evidence for what these prehistoric people ate, in the form of pig bones, apple seeds and carbonised grain.

This view shows the complexity of the cemetery with a body laid out on an excarnation platform, exposed to the elements and birds as part of the funeral process. Men are keeping the site tidy and working on one of the barrows.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

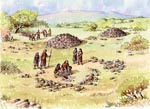

Barrow Site Detail

Barrow Site Detail Brickland Barrow Site Detail, Loughbrickland, Co Down

During upgrading of the main A1 Belfast to Newry road a number of sites were discovered, particularly around Newry and Loughbrickland.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area to the south of Lough Brickland itself, where they uncovered two late bronze age barrow cemeteries.

The cremated remains of 22 men, women and children were recovered from the cemeteries. The artefacts found include whole pottery bowls, polished stone axes, and flint arrowheads. The archaeologists also found evidence for what these prehistoric people ate, in the form of pig bones, apple seeds and carbonised grain.

This view shows a body laid out on an excarnation platform, exposed to the elements and birds as part of the funeral process. Men are working on a barrow in the background.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in the area to the south of Lough Brickland itself, where they uncovered two late bronze age barrow cemeteries.

The cremated remains of 22 men, women and children were recovered from the cemeteries. The artefacts found include whole pottery bowls, polished stone axes, and flint arrowheads. The archaeologists also found evidence for what these prehistoric people ate, in the form of pig bones, apple seeds and carbonised grain.

This view shows a body laid out on an excarnation platform, exposed to the elements and birds as part of the funeral process. Men are working on a barrow in the background.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

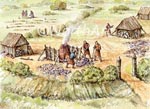

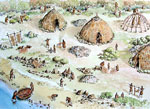

Ballintaggart Neo Site

Ballintaggart Neo Site Ballintaggart Neolithic Site, Loughbrickland, Co Down

During upgrading of the main A1 Belfast to Newry road a number of sites were discovered, particularly around Newry and Loughbrickland.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd and perhaps one of the most exciting excavations was at Ballintaggart, close to Loughbrickland, where three house remains were discovered dating to the Neolithic period.

The view shows how these houses may have looked and the sort of activities that took place by these early farmers.

Much of the investigation work was carried out by the Northern Archaeological Consultancy Ltd and perhaps one of the most exciting excavations was at Ballintaggart, close to Loughbrickland, where three house remains were discovered dating to the Neolithic period.

The view shows how these houses may have looked and the sort of activities that took place by these early farmers.

For more information visit http://www.northarc.co.uk/

Image ©Northern Archaeological Consultancy - Please respect this right

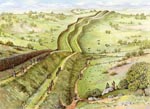

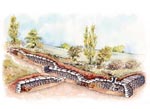

Black Pigs Dyke Being Built

Black Pigs Dyke Being Built The Black Pigs Dyke, Aghareagh West, Co Monaghan

Straddling counties Monaghan, Cavan, Louth, Armagh, Leitrim, Roscommon, Longford and Donegal it is almost impossible to summarise the Black Pig's Dyke in a few paragraphs. It's extensive rows of massive banks and ditches are amongst the oldest, largest and most celebrated land boundaries in prehistoric Europe. In addition, interpretation of these linear earthworks have also proved to be the most elusive.

Although quite scattered, the popular public understanding was that they formed a cohesive and unified boundary for the ancient kingdom of Ulster, a monumental frontier defence that divided the province from the rest of Ireland. Theses views are now disputed by modern archaeology.

The earthworks are also associated with a widespread folk tradition about a cruel schoolmaster with magic powers who was transformed by one of his students into a mystical giant black pig and chased across the countryside, leaving in his wake a large track before drowning in a lake.

For a number of reasons little was done, until relatively recently, to interpret the Black Pig's Dyke and other associated earthworks such as the Dorsey and the Dane's Cast. In the past 30-40 years much has been accomplished by archaeologists in understanding the enigma behind their purpose and, although some interesting proposals have been made, there is still much to be uncovered.

The view shows construction of the Aghereagh West section of the Dyke, one of the best preserved and clearly visible lengths in County Monaghan.

Although quite scattered, the popular public understanding was that they formed a cohesive and unified boundary for the ancient kingdom of Ulster, a monumental frontier defence that divided the province from the rest of Ireland. Theses views are now disputed by modern archaeology.

The earthworks are also associated with a widespread folk tradition about a cruel schoolmaster with magic powers who was transformed by one of his students into a mystical giant black pig and chased across the countryside, leaving in his wake a large track before drowning in a lake.

For a number of reasons little was done, until relatively recently, to interpret the Black Pig's Dyke and other associated earthworks such as the Dorsey and the Dane's Cast. In the past 30-40 years much has been accomplished by archaeologists in understanding the enigma behind their purpose and, although some interesting proposals have been made, there is still much to be uncovered.

The view shows construction of the Aghereagh West section of the Dyke, one of the best preserved and clearly visible lengths in County Monaghan.

For more information visit http://www.monaghan.ie/en/portal/

Image ©Monaghan County Council - Please respect this right

Ballyutoag Flint Site

Ballyutoag Flint Site Ballyutoag Flint Site, Belfast, Co Antrim

This view shows a typical Neolithic Flint working site positioned beside a small river. It is a conjectural setting and was included as an insert for the Ballyutoag Court Cairn and surrounding area.

As well as flint knapping (the practice of shaping flint tools by chipping small pieces off with another piece of stone), our small group from the Neolithic period are preparing animal skins and stitching them for clothing.

As well as flint knapping (the practice of shaping flint tools by chipping small pieces off with another piece of stone), our small group from the Neolithic period are preparing animal skins and stitching them for clothing.

For more information visit http://www.belfasthills.org

Image ©Belfast Hills Partnership - Please respect this right

Ballyutoag Neo Site

Ballyutoag Neo Site Ballyutoag Neolithic Site, Belfast, Co Antrim

Also known as the Hanging Thorn Cairn, tradition says that a man was hanged from it in 1798.

The Cairn itself is the remains of a court tomb. Only the stones of the forecourt remain in situ but there are many other separated large stones which may be the remains of the burial chamber.

Part of the forecourt of this court tomb was excavated in 1937, revealing some Neolithic pottery, a flint scraper and some Iron Age or Medieval pottery. The site consists of a roughly semi-circular court formed by at least eight possible stones, some very large. Two portal stones with a sill between them and four recumbent stones lie further down the slope, along the estimated line of the gallery. The tomb is dated around 4000 BC.

Our view shows the court cairn in the foreground along with two Neolithic settlements beyond. Between the settlement on the left and the cairn, people are working close to the Flush River (see Ballyutoag Flint Site).

The Cairn itself is the remains of a court tomb. Only the stones of the forecourt remain in situ but there are many other separated large stones which may be the remains of the burial chamber.

Part of the forecourt of this court tomb was excavated in 1937, revealing some Neolithic pottery, a flint scraper and some Iron Age or Medieval pottery. The site consists of a roughly semi-circular court formed by at least eight possible stones, some very large. Two portal stones with a sill between them and four recumbent stones lie further down the slope, along the estimated line of the gallery. The tomb is dated around 4000 BC.

Our view shows the court cairn in the foreground along with two Neolithic settlements beyond. Between the settlement on the left and the cairn, people are working close to the Flush River (see Ballyutoag Flint Site).

For more information visit http://www.belfasthills.org

Image ©Belfast Hills Partnership - Please respect this right

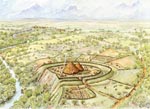

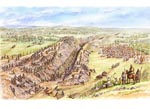

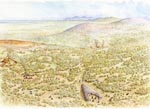

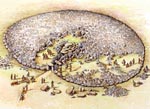

Prehistoric Derry

Prehistoric Derry Prehistoric Derry, Derry, Co Londonderry

This was one of five illustrations I prepared for Ruairi O'Baoill's beautiful book on Ulster's maiden city- 'Island City: The Archaeology of Derry/Londonderry'.

Although the city is known better for its 17th century history it was believed to have had a rich prehistory, mainly due to it's revered location.

Unfortunately no substantive prehistoric monuments have as yet been uncovered, nevertheless it is considered that the island would have had a henge possibly at the highest point (where the walled city now stands) and would have been approached by a long ceremonial way, perhaps partly lined with upright stones.

At this time Derry would have been actually separated from the mainland and only accessible by boat. At the southern extremity, where the only access would have been possible or permitted, there may have been a cemetery with ring barrows and a court cairn.

This is therefore a very conjectural view - but such is archaeological reconstruction!

Although the city is known better for its 17th century history it was believed to have had a rich prehistory, mainly due to it's revered location.

Unfortunately no substantive prehistoric monuments have as yet been uncovered, nevertheless it is considered that the island would have had a henge possibly at the highest point (where the walled city now stands) and would have been approached by a long ceremonial way, perhaps partly lined with upright stones.

At this time Derry would have been actually separated from the mainland and only accessible by boat. At the southern extremity, where the only access would have been possible or permitted, there may have been a cemetery with ring barrows and a court cairn.

This is therefore a very conjectural view - but such is archaeological reconstruction!

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

McArts Fort

McArts Fort McArts Fort, Belfast, Co Antrim

McArts Fort probably owes its name to a former Celtic chieften Eochaid mac Ardgail from the late 9th century.

It exploits a natural promontory on the steep southern face of Ben Madigan, known locally as the Cave Hill. It is also likely that the site was occupied as early as the Bronze or Iron Age, when it would have been classed as a promontory fort.

This view looking south shows McArts Fort during a Celtic inauguration ceremony. This is focussed on a small 'Royal' group on the high ground near the precipice. The visitor today can still identify the double ditches that protect this area and signs of entrances on the western side of the fortifications. This would have been the main route to the fort, accessed from the valley below.

The background shows the Lagan estuary, now occupied by reclaimed land and the Port of Belfast.

It exploits a natural promontory on the steep southern face of Ben Madigan, known locally as the Cave Hill. It is also likely that the site was occupied as early as the Bronze or Iron Age, when it would have been classed as a promontory fort.

This view looking south shows McArts Fort during a Celtic inauguration ceremony. This is focussed on a small 'Royal' group on the high ground near the precipice. The visitor today can still identify the double ditches that protect this area and signs of entrances on the western side of the fortifications. This would have been the main route to the fort, accessed from the valley below.

The background shows the Lagan estuary, now occupied by reclaimed land and the Port of Belfast.

For more information visit http://www.belfasthills.org

Image ©Belfast Hills Partnership - Please respect this right

Souterrain

Souterrain Souterrain

An Irish souterrain, literally 'under ground', dates primarily from the 6th century onwards and is frequently associated and contemporary with other Early Christian monuments such as raths and cashels, both being types of ring forts.

Although their purpose is not clearly defined, they are thought likely to be for storing food or for a refuge during an attack.

In most cases the entrance is small and concealed in some way and is usually accessible from within the ring fort. The example shown here, albeit generic, is based on an actual site. The main entrance is on the left and is only large enough for one person to crawl through at a time. Further along is a 'drop hole creep' with some further 'simple creeps' punctuating the passage and also giving access to side passages. The purpose of the creeps is to discourage any unwelcome visitors. At the end of the passage is a ventilation shaft, made sufficiently small that an adult would be unable to access the souterrain.

Although their purpose is not clearly defined, they are thought likely to be for storing food or for a refuge during an attack.

In most cases the entrance is small and concealed in some way and is usually accessible from within the ring fort. The example shown here, albeit generic, is based on an actual site. The main entrance is on the left and is only large enough for one person to crawl through at a time. Further along is a 'drop hole creep' with some further 'simple creeps' punctuating the passage and also giving access to side passages. The purpose of the creeps is to discourage any unwelcome visitors. At the end of the passage is a ventilation shaft, made sufficiently small that an adult would be unable to access the souterrain.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

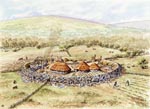

Ballyaghagan c1100

Ballyaghagan c1100 Ballyaghagan Cashel c1100, Belfast, Co Antrim

Ballyaghagan Cashel featured recently in a 'Big Dig' project managed by the Belfast Hills Partnership and Queens University, Belfast. It involved a community excavation with more than 400 people actively participating at the site on the Upper Hightown Road.

No work had ever been carried out on the site before and initially it was thought to be a straightforward cashel, a circular stone enclosure dating to the Early Christian period (c500-1000AD).

This reconstruction shows the site c1100 when it is still in use as a small hill farm.

No work had ever been carried out on the site before and initially it was thought to be a straightforward cashel, a circular stone enclosure dating to the Early Christian period (c500-1000AD).

This reconstruction shows the site c1100 when it is still in use as a small hill farm.

For more information visit http://http://www.belfasthills.org

Image ©Belfast Hills Partnership - Please respect this right

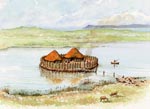

Crannog

Crannog View of a Crannog

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

A crannog is an artificial island enclosure dating from the Irish Early Christian period (c500-1000AD).

The island would have been accessed by boat or by a partly submerged causeway.

A remarkable crannog was recently found at Cherrymount, Enniskillen during road improvements.

A crannog is an artificial island enclosure dating from the Irish Early Christian period (c500-1000AD).

The island would have been accessed by boat or by a partly submerged causeway.

A remarkable crannog was recently found at Cherrymount, Enniskillen during road improvements.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

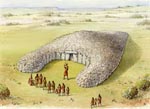

Court Cairn

Court Cairn View of a Court Cairn

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Court cairns date to the Neolithic period (c4000BC - 2500BC) and are identified by having horn shaped extensions at the front forming a court around the entrance.

This example is of the well preserved Court Cairn at Tamnyrankin.

Court cairns date to the Neolithic period (c4000BC - 2500BC) and are identified by having horn shaped extensions at the front forming a court around the entrance.

This example is of the well preserved Court Cairn at Tamnyrankin.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

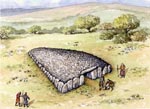

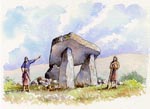

Wedge Tomb

Wedge Tomb View of a Wedge Tomb

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Wedge tombs get their name from the characteristic wedge shape when viewed from above. The entrance is at the wider end of the wedge and leads into a chamber where the remains are placed.

Wedge tombs date to the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age period (c2500BC - 2000BC).

Wedge tombs get their name from the characteristic wedge shape when viewed from above. The entrance is at the wider end of the wedge and leads into a chamber where the remains are placed.

Wedge tombs date to the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age period (c2500BC - 2000BC).

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

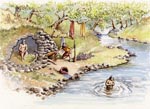

Sweat House

Sweat House View of a Sweat House

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Sweat houses were the prehistoric equivalent to saunas - thought to date back to the Bronze Age (c2500BC).

They were normally constructed in secretive locations for privacy and were near water so that the users could emerge and plunge into this to wash.

A fire was lit inside the chamber, which was very small, and after a while the embers were raked out and the sweaters squeezed through a narrow creep entrance, pulling a curtain or door closed to retain the heat.

Sweat houses were the prehistoric equivalent to saunas - thought to date back to the Bronze Age (c2500BC).

They were normally constructed in secretive locations for privacy and were near water so that the users could emerge and plunge into this to wash.

A fire was lit inside the chamber, which was very small, and after a while the embers were raked out and the sweaters squeezed through a narrow creep entrance, pulling a curtain or door closed to retain the heat.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Stone Circle

Stone Circle View of a Stone Circle

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

The enigmatic stone circle is believed to date from the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age period but other than that their purpose seems to vary from site to site although most would agree that they were built for ceremonial reasons.

They are commonly accompanied by straight lines of stones called alignments which further suggest some astronomical significance.

It is very common to have several stone circles and alignments beside each other as seen at Beaghmore, Co Tyrone.

The enigmatic stone circle is believed to date from the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age period but other than that their purpose seems to vary from site to site although most would agree that they were built for ceremonial reasons.

They are commonly accompanied by straight lines of stones called alignments which further suggest some astronomical significance.

It is very common to have several stone circles and alignments beside each other as seen at Beaghmore, Co Tyrone.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Rath

Rath View of a Rath

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Raths are the commonest archaeological sites in Ireland, dating mostly to the Early Christian period (c500-1000AD) being early farms with a defensive bank and ditch. Sometimes there were multiple banks and there is also evidence to suggest the banks of some raths may have had a palisade for additional security.

Animals were kept outside the enclosure but may have been brought in at night to prevent them being stolen.

Some raths had underground storage tunnels called soutterains.

Raths are the commonest archaeological sites in Ireland, dating mostly to the Early Christian period (c500-1000AD) being early farms with a defensive bank and ditch. Sometimes there were multiple banks and there is also evidence to suggest the banks of some raths may have had a palisade for additional security.

Animals were kept outside the enclosure but may have been brought in at night to prevent them being stolen.

Some raths had underground storage tunnels called soutterains.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Portal Tomb

Portal Tomb View of a Portal Tomb

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Perhaps one of the most distinctive Neolithic megaliths (new stone age large stone monuments) portal tombs, also known as dolmens, are characterised by normally a tripod of upright columns with a large flat capstone on top.

Like most megaliths their purpose was for burial, the remains being brought inside through the two large stone columns at the front - called the portal.

There is some debate as to whether the structure would have been covered in a stone cairn or earth mound, but still keeping the portal exposed.

Perhaps one of the most distinctive Neolithic megaliths (new stone age large stone monuments) portal tombs, also known as dolmens, are characterised by normally a tripod of upright columns with a large flat capstone on top.

Like most megaliths their purpose was for burial, the remains being brought inside through the two large stone columns at the front - called the portal.

There is some debate as to whether the structure would have been covered in a stone cairn or earth mound, but still keeping the portal exposed.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Passage Grave

Passage Grave View of a Passage Grave

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Passage graves date from the Neolithic (new stone age) period and are amongst the largest of the megalithic (large stone) tombs in Ireland.

They consist of a long tunnel, or passage, with stone sides (orthostats) and ceiling that leads to a chamber or number of chambers where the remains are laid.

The passage is then covered with a large cairn bordered by large footstones, sometimes with carvings.

Passage graves date from the Neolithic (new stone age) period and are amongst the largest of the megalithic (large stone) tombs in Ireland.

They consist of a long tunnel, or passage, with stone sides (orthostats) and ceiling that leads to a chamber or number of chambers where the remains are laid.

The passage is then covered with a large cairn bordered by large footstones, sometimes with carvings.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Linear Earthwork

Linear Earthwork View of a Linear Earthwork

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

More information will be added here shortly.

More information will be added here shortly.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Henge

Henge View of a Henge

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

More information will be added here shortly.

More information will be added here shortly.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Church Bay Grave

Church Bay Grave Church Bay Bronze Age Grave, Rathlin, Co Antrim

These illustrations were prepared for inclusion in the Archaeological Survey of Rathlin, just recently published.

The fields flanking Church Bay were a particular focus of Early Bronze Age activity.

This one took the form of cist (a box formed by flat stones) which was then covered with a cairn.

People of this period were buried along with pottery which helped archaeologists to date the graves.

The fields flanking Church Bay were a particular focus of Early Bronze Age activity.

This one took the form of cist (a box formed by flat stones) which was then covered with a cairn.

People of this period were buried along with pottery which helped archaeologists to date the graves.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Cashel

Cashel View of a Cashel

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Cashels are contemporary with their much more numerous raths and date from mostly the Irish Early Christian period (c500-1000AD), the main difference being that they were mostly confined to rockier areas and were therefore stone built.

The buildings inside were also more than likely stone built with thatched roofs.

Cashels are contemporary with their much more numerous raths and date from mostly the Irish Early Christian period (c500-1000AD), the main difference being that they were mostly confined to rockier areas and were therefore stone built.

The buildings inside were also more than likely stone built with thatched roofs.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Cairn

Cairn View of a Cairn

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

A Cairn is a man made covering of stones, normally to cover a burial tomb and are therefore distinct from Barrows, which are mostly mounds of earth.

The illustration shows the remains having been placed in a stone box or 'cist' and a capstone being placed over this.Other helpers are in the background bringing in the stones that will form a cairn over this burial.

Cairns date from the Middle and Late Bronze Age and also extend into the Iron Age (1700 BC to AD 400)

A Cairn is a man made covering of stones, normally to cover a burial tomb and are therefore distinct from Barrows, which are mostly mounds of earth.

The illustration shows the remains having been placed in a stone box or 'cist' and a capstone being placed over this.Other helpers are in the background bringing in the stones that will form a cairn over this burial.

Cairns date from the Middle and Late Bronze Age and also extend into the Iron Age (1700 BC to AD 400)

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Burnt Mound

Burnt Mound View of a Burnt Mound

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

Burnt Mounds are named after the residue left from the practice of heating stones in a fire then plunging them into a trough of water. The hot water was used mostly for cooking and periodically the shattered stones and other detritus would be cleared out of the trough and deposited nearby, forming a crescent shaped mound.

Radiocarbon dating of the material dates these sites from the late Neolithic until the early Medieval periods.

Burnt Mounds are named after the residue left from the practice of heating stones in a fire then plunging them into a trough of water. The hot water was used mostly for cooking and periodically the shattered stones and other detritus would be cleared out of the trough and deposited nearby, forming a crescent shaped mound.

Radiocarbon dating of the material dates these sites from the late Neolithic until the early Medieval periods.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Belfast Neolithic

Belfast Neolithic Neolithic Belfast

These illustrations were completed in 2010 to be used in Ruairi O'Baoills Archaeological Story of Belfast. These aerial views show the Lagan Valley area from the very earliest settlers until the 17th century.

They locate important archaeological sites in the surrounding area and help to explain many of the place names so familiar to Belfast residents today.

By the Neolithic period (c4000BC - 2500BC) the population had increased and small farms developed.

These people also built stone tombs such as cairns and portal graves and there is also evidence to suggest that there were organised settlements - shown here on the Malone Ridge.

The large circular site in the background near the Lagan is the Giant's Ring.

They locate important archaeological sites in the surrounding area and help to explain many of the place names so familiar to Belfast residents today.

By the Neolithic period (c4000BC - 2500BC) the population had increased and small farms developed.

These people also built stone tombs such as cairns and portal graves and there is also evidence to suggest that there were organised settlements - shown here on the Malone Ridge.

The large circular site in the background near the Lagan is the Giant's Ring.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Belfast Mesolithic

Belfast Mesolithic Mesolithic Belfast

These illustrations were completed in 2010 to be used in Ruairi O'Baoills Archaeological Story of Belfast. These aerial views show the Lagan Valley area from the very earliest settlers until the 17th century.

They locate important archaeological sites in the surrounding area and help to explain many of the place names so familiar to Belfast residents today.

This view shows the Mesolithic shoreline - considerably higher than what it is today - with the Bog Meadows flooded and the Malone Ridge forming the higher ground between it and the Lagan.

This would have been suitable locations for the hunter/gatherers and finds from this area confirm this early occupation.

They locate important archaeological sites in the surrounding area and help to explain many of the place names so familiar to Belfast residents today.

This view shows the Mesolithic shoreline - considerably higher than what it is today - with the Bog Meadows flooded and the Malone Ridge forming the higher ground between it and the Lagan.

This would have been suitable locations for the hunter/gatherers and finds from this area confirm this early occupation.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Barrow

Barrow View of a Barrow

This illustration was prepared primarily for use in booklets to be distributed to local farmers so that they can identify features on their land that represent valuable elements of our heritage. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency is committed to protect the built environment and as such work to preserve and carefully manage these irreplaceable resources.

There are many examples of monuments which are termed ring barrows, and comprise a circular or oval-shaped mound covering a burial (usually a stone cist) enclosed by various configurations of banks and ditches.

These are part of the Bronze Age burial tradition but radiocarbon dating has indicated that they predominate during the Middle and Late Bronze Age and also extend into the Iron Age (1700 BC to AD 400).

There are many examples of monuments which are termed ring barrows, and comprise a circular or oval-shaped mound covering a burial (usually a stone cist) enclosed by various configurations of banks and ditches.

These are part of the Bronze Age burial tradition but radiocarbon dating has indicated that they predominate during the Middle and Late Bronze Age and also extend into the Iron Age (1700 BC to AD 400).

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Mesolithic Camp

Mesolithic Camp Mesolithic Camp, Conjectural Location

This view shows a detail of a Mesolithic settlement and what activities these ancient people did in order to survive.

This search for food forced these early inhabitants to move around depending on the seasons. Evidence of their existence is found in some excavated settlements, where their huts and middens (rubbish heaps) show how they sheltered and fed.

Many Mesolithic coastal settlements like this one were inundated as the sea level rose in the period after the Ice Age. As the land started to rise itself, many of these drowned settlements were exposed on the raised beaches and flint tools can be found on these features.

This search for food forced these early inhabitants to move around depending on the seasons. Evidence of their existence is found in some excavated settlements, where their huts and middens (rubbish heaps) show how they sheltered and fed.

Many Mesolithic coastal settlements like this one were inundated as the sea level rose in the period after the Ice Age. As the land started to rise itself, many of these drowned settlements were exposed on the raised beaches and flint tools can be found on these features.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

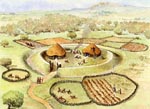

Neolithic Farm

Neolithic Farm Neolithic Farm, Conjectural Location

The first real farmers that settled in Ireland did so around 4000BC. These people, as well as building more permanent shelter, organised proper farms into field systems where they both raised livestock and grew crops. In this way they were able to remain in the same area all year round, unlike their Mesolithic predecessors.

Much of the evidence of these settlers was not from their farms but from the inigmatic stone monuments that they left - the Megaliths. These early feats of structural engineering include Passage Graves, Portal Tombs (Dolmens) and Court Tombs, one of which is being constructed in this view.

Much of the evidence of these settlers was not from their farms but from the inigmatic stone monuments that they left - the Megaliths. These early feats of structural engineering include Passage Graves, Portal Tombs (Dolmens) and Court Tombs, one of which is being constructed in this view.

For more information visit http://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/

Image ©Department for Communities - Please respect this right

Google Maps are available for relevant items however these can slow down your browsing experience. Select Maps using the button.

| About | Process | Prehistoric | Medieval | Later | People | Landscapes | Terms of Use | Links | Contact |

| © Philip Armstrong, Larne, N.Ireland 2022 This site only uses functional cookies |